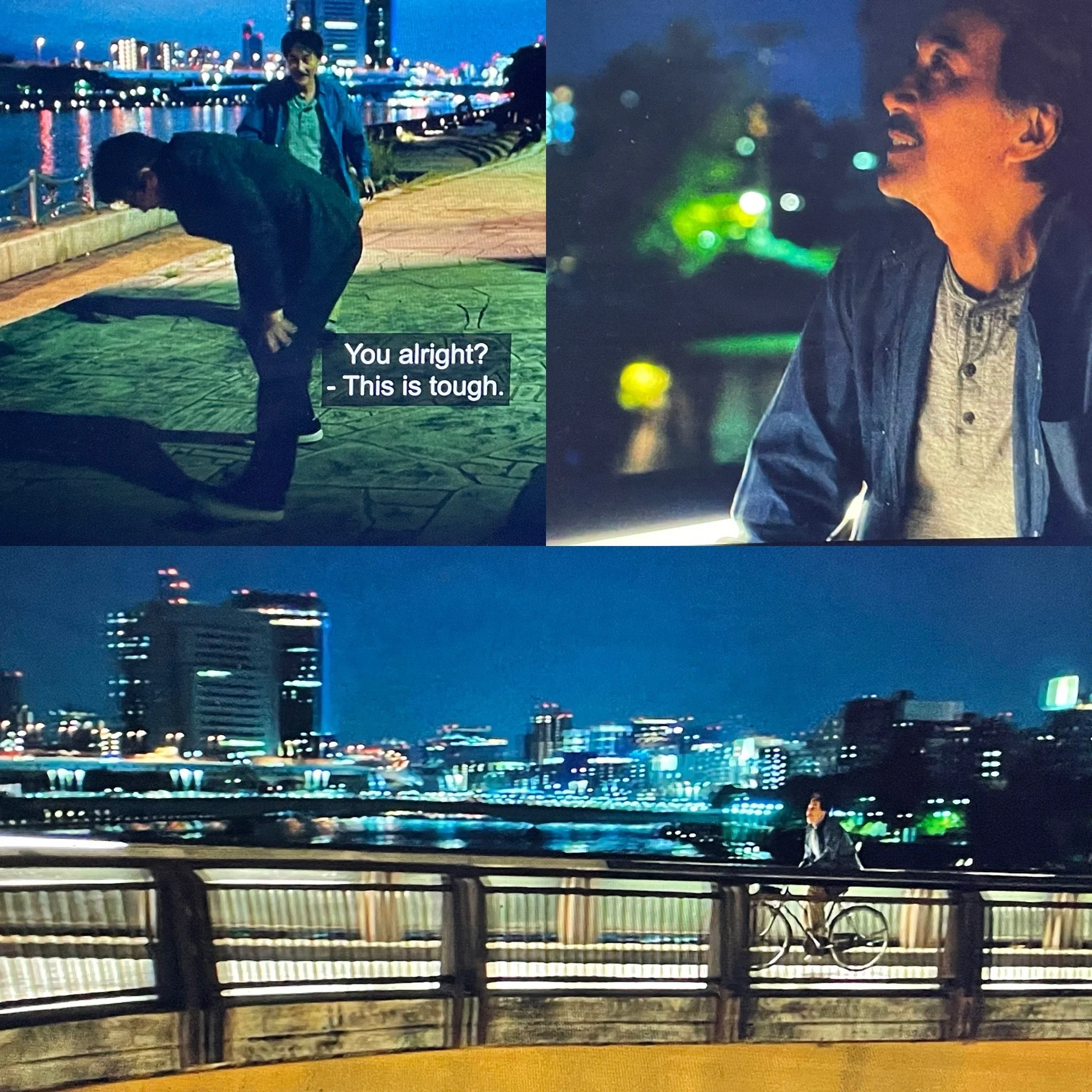

"Perfect Days" Directed by Wim Wenders, Movie Review

Substack podcast-style reading here.

I’ve always found it easy to agree with the guidance that, “How you do one thing is how you do everything,” since it follows that a starting point of generosity or self-interest, curiosity or assumptions, engagement or laziness, will issue energy in similar form.

In turn, no act becomes too small or large, as consistency in the places one chooses to act from grows a frame on which anything we do speaks to, then builds, on cores of service or exploitation, gratitude or prejudice.

Case in point: in Wim Wenders’ 2023 film, “Perfect Days,” I find no shortage of meaning in the fact that the launch of The Tokyo Toilet project served as the instigator for one of the best films I’ve ever seen.

The project, seeing its first of 17 toilets to date installed in 2020, was launched as a public-service effort to bring aesthetics and altruism to a problem as long-standing as any in human society.

The results have given the world a joyful approach to a need that, on paper, seems hard to be beat when it comes to the mundane.

Even so, every community has had to deal with the unavoidable issue of excrement in a way that preserves health and, ideally, holds discretion around a very private matter.

And with the triumph and role model that the Tokyo Toilet has turned out to be, “Perfect Days” mirrors a similarly noteworthy approach to challenges both pervasive and passing, large and small, with poignant focus on how we take care of ourselves and others.

Wenders lands these themes well in the genre of slow cinema in “Days,” a somewhat risky choice, as it has given us the triumphs we see in nearly every Terrence Malick film, or stumbles in gorgeous-but-empty screen savers like 2020’s “Gunda,” or endurance-testing experiments like 2002’s “Gerry.”

When successful, slow cinema invites viewers to stories told through long, wandering shots that not only immerse, but lift audiences to places that grow the span of one’s outlook on life outside of the film in a way set apart from other genres.

I would argue that this is because our real, experiential lives, if we are gifted to have sight, manifest one long, wandering shot, a viewpoint unbroken even by sleep, since we see plenty of things there, too, even the dark, imageless spaces between dreams offering stillness one can draw much from.

In this life, our viewpoints are aimed by or at all kinds of vantage points that we draw what we will from, gaining and losing much, but ultimately losing everything in the process.

So, whenever possible, sharp discernment on what and who we share the view with has to be taken seriously, which also marks the choices of a prudent film director, too.

And, if skill has met courage, we get to see new benchmarks for what the medium can accomplish through visual techniques that, to me, express authenticity around what life is like better than any other in film.

The misses in slow cinema arrive, in my opinion, when the journey selects for an image, sits, and moves on without consequence. Our investment of attention and time goes unacknowledged when nothing moving, intriguing, or new has been revealed, a passing grade that I would extend to any piece of art, for that matter.

Doing so does great at boring audiences, especially me, and bares a piece that has settled for spectacle over pushing the craft.

I welcome disagreement, but I found none of this in play with the journey we get to experience along with Hirayama in “Days,” a protagonist Kōji Yakusho balances between understatement and charisma as near to perfection as I’ve ever seen.

Every move Yakusho turns in, from scrubbing to selling a treasured cassette tape to help a friend, shows a deftness at subtly that struck me as hypnotic, convincing to the point that we forget there’s a script in play.

In Hirayama, Yakusho brings us on a ride with a man genuinely fulfilled by a quiet life and small joys. Hirayama knows what he wants and is grateful for everything he gets to include in his life, from photos of sunlight on trees to views of the ocean on his commute, from great literature to rock music, friendly business owners to young people at turns quirky and frantic.

This said, going overboard can find lesser artists in this space, but Yakusho never lets appreciation overflow to the saccharine, keeping sound footing on a meditative foundation of gratitude and positivity, no matter who or what comes his way.

Throughout the film, Hirayama comes across a wide range of neighbors in Tokyo, some with little self-awareness and solidly funny moments, to his sister, the only other character who seems to know his back story, and alludes to a capacity for a more affluent and accomplished life if he wanted it.

Hirayama might indeed be fleeing or hiding from something much larger than his life would seem to assume. But, he is just as likely trading an understanding of what that might require for a place that keeps him stable and happy.

By including these details, Wenders weaves conflict with mystery in Hirayama’s life. He could be doing more outside of cleaning public spaces, but decides not to, and meets this choice with care and compassion.

The sister’s tone and presence indicates there is likely a lot of class and capital in his background. A falling out with a father is brought up and addressed flatly, closed quickly. Whether Hirayama’s life choices are made because of trauma or to spite past incidents is never made clear.

By way of an indirect answer, the ending of the film brings Hirayama to an indulgent night out with a terminally-ill man. The character comments on the mysteries that haunt us in our current time, and will continue to confound others in their times, unanswerable questions larger than the passing durations we get to spend meeting and wrestling with them.

Hirayama steps into these profound moments, of which there are many, with full attention given to the people he shares them with, serving with a listening ear and encouragement whenever possible.

The meta-messages are essential, wherein the viewer is asked what they bring to moments like these, as well as assumptions made about a person who works in sanitation.

What are our reactions to extended stays in turmoil and delight?

Every human has their journey and choices to bear, and the choices Hirayama has made to be alone and work as a custodian come at a price, but by all indications add to the beauty and contentment he enjoys and exudes.

A true gift in its vision, on par with where I hold "A Hidden Life" as a compass for morality, I found in "Perfect Days" a handbook for day-to-day life, Hirayama a high point for navigating the pain points and unfairness we get in all kinds of ways in our world.

In Yakusho’s performance, I see a human at once grounded and gliding on patience and humility, kindness and service, working through times that look a lot like ours, but in the very, very eventful times in which I’m writing this, I am grateful to have this example in my life: a person in a mode of donning care as a verb, discerning in perspective, and taking time to foster and reflect as much grace as possible.