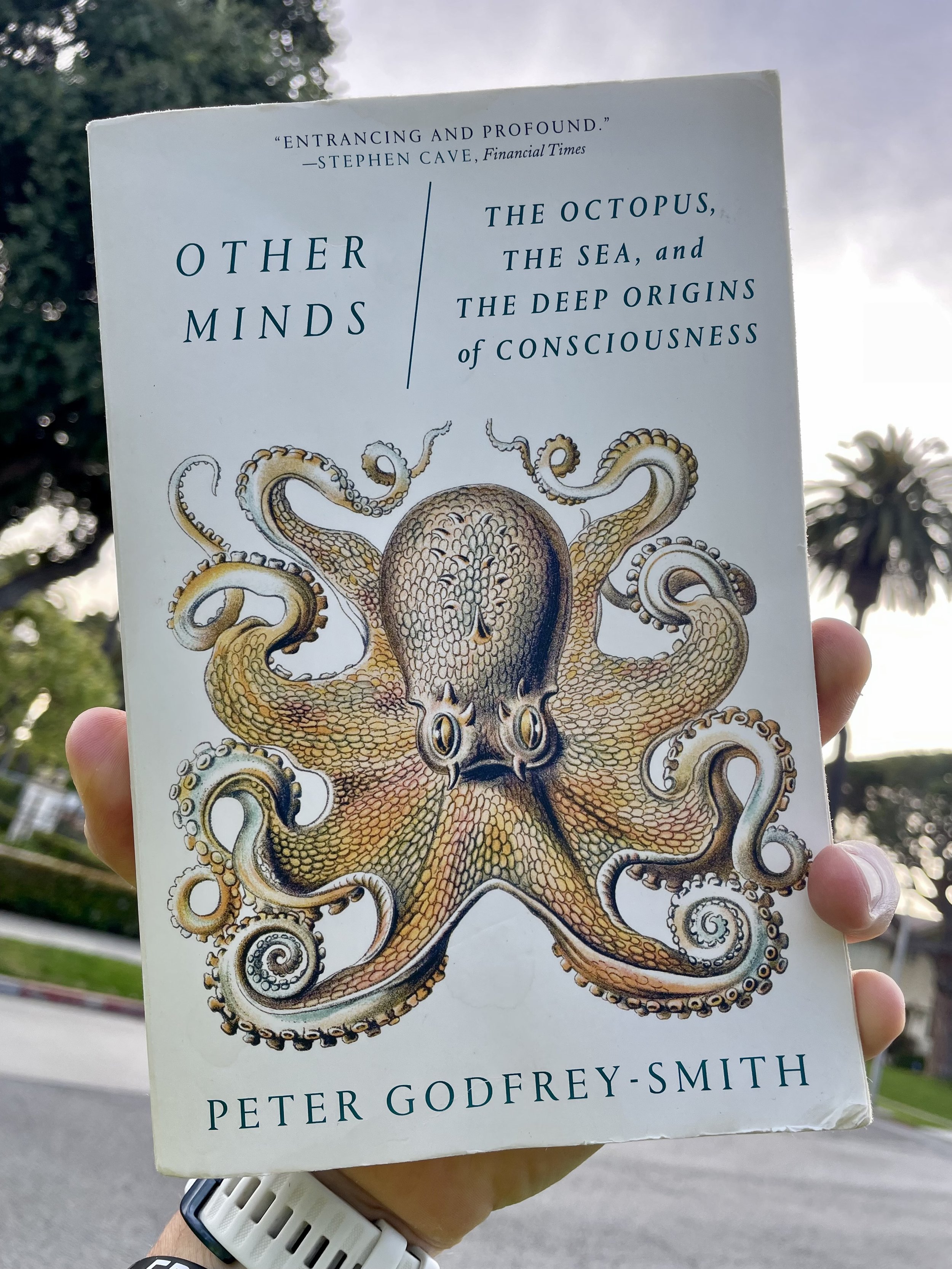

"Other Minds" by Peter Godfrey-Smith

A place called Octopolis, a real place with a perfect name, sets a similarly perfect, literal, and figurative springboard for Peter Godfrey-Smith to dive into and launch a wellspring of query and discovery from the very start of his book, Other Minds.

This unique haven, located in Jervis Bay, off the southeast coast of Australia, sets a compelling starting line for Godfrey-Smith, a philosopher of science and proficient diver, in a remarkable location where the common Sydney octopus, usually opting for solitude, has settled in large numbers.

In this very unusual behavior for the species, an ideal entry point is opened for the thorough and expansive query Minds proceeds to make into the evolutionary history, inner workings, and subjective experience of cephalopods of all types.

From this thesis, Godfrey-Smith puts light on all kinds of fascinating territory as close to home as one can get, as the framework, functions, and development of our own minds is examined to at least the same depth and insight alongside our very, very distant relations.

Once the table is set, however, our seats are pulled away fairly quickly, in light of how the brains and neural networks of the modern octopus, squid, nautilus, and cuttlefish branched from a different segment of the evolutionary tree than ours entirely.

It’s a significant reframe that gives one much to consider when reading that complex brains have developed twice in Earth’s history, selecting for us and the hominid franchise, and much earlier in these incredible members of the mollusca phylum, sharpening into the curious, combative, tool-using, and often-mysterious cephalopods.

Among many significant contrasts and abilities boasted by this totally divergent take on neutral networks, Godfrey-Smith speaks on the unique distribution of autonomy throughout the octopus body, a unique doling out that goes so far as to effect what he describes as “curiously divorced” arms, offering organs that might even have short-term memories of their own.

This arrangement makes the octopus brain something of a manager, controlling levels of appraisal, adjustment, and trust in the actions of eight teammates reporting back to the central hub.

I found it incredible to read about how independent these arms can be at times, some even having a preference or distaste for certain food items, bringing eyebrow-raising moments where individuals are caught between disagreements with their own bodies.

It’s is a fun image, doing well to express moments any person can relate to, say, one hand lifting a Reese’s cup, only for the other to take it and put it back down, “C’mon, live a little,” then, “Please, there’s nothing we need here,” the other hand retrieving it already, “Just one, I swear,” and so forth.

For me, it’s in these types of insights that I found one of the most valuable elements of the book: an open invitation to imagination.

To read Minds is to sit with the variations and extraordinary abilities our several-times-removed relatives have inherited, meeting entirely different planes and demands than those that bind the hominid line.

Like any significant step outside of ourselves, at best a creative strain of empathy arises, asking us to see the world and ourselves differently. To do so with our fellow humans is a valuable exercise in understanding others.

Taking this inroad into a different species welcomes another umwelt entirely, or the unique experience brought about by a particular life form’s respective needs, attributes, experience, and environment.

These points of contact with reality, according to Godfrey-Smith and current thinking on the topic, are caught by way of embodied cognition, or the digestion of raw data gathered, then acted on, based on information received and made useful by a given physical system.

With these types of steps outside of ourselves, the mind reels at the brutal, beautiful, and curious lives cephalopods of all types must lead. I also found myself wondering about what can be read into the behaviors of the many different cephalopods Godfrey-Smith meditates on, especially in the way cuttlefish seem to give an intentional cold shoulder of sorts to human visitors.

This expression was especially interesting to me, since cuttlefish show an extraordinary amount of brain capacity in cephalopods, which is, of course, not directly proportional to intelligence, but noteworthy. Cuttlefish also engage with their prey less than their relations, perhaps a sign of practicality taking priority.

And, amazingly, they display REM during sleep, changing colors as they do so, which might infer dreams cast onto the skin’s top-most layer of chromatophores.

Therefore, in the cuttlefish, we have a true marvel among marvels to consider, a life given, elected or not, to visually expressing their dreams to the world across bodies as canvasses, in colors and forms many an artist has aimed for, while still mature enough in their waking lives to be unimpressed by the entertainment of their fellows.

And, though they have to be aware of our presence when we come close, they let humans know that they have nothing for us, fleeing or fear as far from their minds as any acknowledgement.

To pull a speculative thread, one wonders how much the cuttlefish connects between the plastics, gases, and invasiveness of these incursions with the essences of plastics, gases, and pervasive invasiveness they must sense in their homes, all seeping down from above, the same direction we descend from, loudly, at an ever-increasing rate, into habitats that carry none of these elements on their own.

For a being as outweighed and outnumbered as they are, can we look at the cuttlefish’s open disregard as embarrassment for our species? Is this turning of the eyes a free choice to look at more of the creature’s home, a selection for the open blue over the pain that is every other interaction with a race that forces so much of itself on them already?

As much conjecture and projection as I’m at with this, Godfrey-Smith always keeps to his lane, speaking on steadier ground, even in lives as bizarre and outside of ours as he gets.

Indeed, I have to admire his humility throughout, the qualifiers used especially around these inner workings, for example, around new maps being set to the functional systems of imagination itself, parts that “may arise purely from the imagination itself, and only coincidentally resemble products of the ancient mechanisms.”

Passages like this fence in pure guesswork to how we really can’t “see” these items in action, but can and do test them to bring them out of pure speculation but this side of proven.

With the clear eyes and authority that come with this approach, Other Minds in the end is a trusted joy, as adventurous and edifying as any serious approach to evolution and philosophy can be, in my experience.

Sure, no one’s work is going to be perfect, and there are long bouts of non-cephalopod wanderings that stray far and quite a ways down from the topic at hand.

That said, this sort of roaming off the path was more than forgivable for me, and marks a thinker who is genuinely curious about everything and ready for anything. And to follow Godfrey-Smith along these side-missions brought me no loss in the enlightenment and thoughtful provocations I found in the rest of the book.

Lose the plot all you want, just don’t waste my time, and I’ll stick around, happily.

And if I get to spend more time having my imagination and appreciation for cephalopods flexed and made stronger, I’m only grateful, and look forward to more of the same.