"Madame Bovary" by Gustave Flaubert

Madame Bovary by Gustav Flaubert

A clear cornerstone of literature and deeply unpleasant, I certainly got a lot out of Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, both as a podium-performance for its time, a major influence for all time, and the part-gauntlet-part-call-to-arms thrown down for serious writers ever since by the rigor its author poured into the piece.

To be clear, the notoriety around the mastery of the craft in play is beyond doubt. The beauty and inventiveness of the language and imagery is some of the best I’ve come across, anywhere.

As much as I know gets lost in translation, passages like the following speak for themselves from some of the most elegant heights one could ask for:

“Daylight came down the chimney, laying a velvet sheen on the soot in the fireplace and tinging the cold ashes with blue…”

“At sunset you breathe the scent of lemon trees on the shore of a bay…”

“Her will is like the veil on her bonnet, fastened by a single string and quivering at every breeze that blows. Always there is a desire that impels and a convention that restrains.”

Beautiful passages, period.

That said, Flaubert’s negativity towards his characters, from side-swiping bitchiness to direct and uncomfortable skewering, struck me throughout the story as needless and excessive.

I’d be impressed if I ever come across a writer who hates their characters more, starting with Charles, the main protagonist besides the titular Emma Bovary.

The unwarranted jabs arrive early, with Charles taking “on a doleful sort of expression that made it almost interesting,” from the get-go, framing a man as boring already before his father-in-law, Rouault, thinks of him as “rather a wisp of a man, to be sure, not quite the son-in-law he could have wished for.”

More of the same is laid quite liberally throughout the book, turning especially cruel at an end that sees Emma dead.

Charles, steeped in mourning, presents a place Flaubert sees fit to show the bereaved “staring idiotically at the stone floor,” followed by a short, miserable curtain call on the life of a man struggling to make up for his wife’s indiscretions, ending with a death and subsequent autopsy that sees the coroner take part in a metaphor woefully on-the-nose when he opens “up the body but found nothing.”

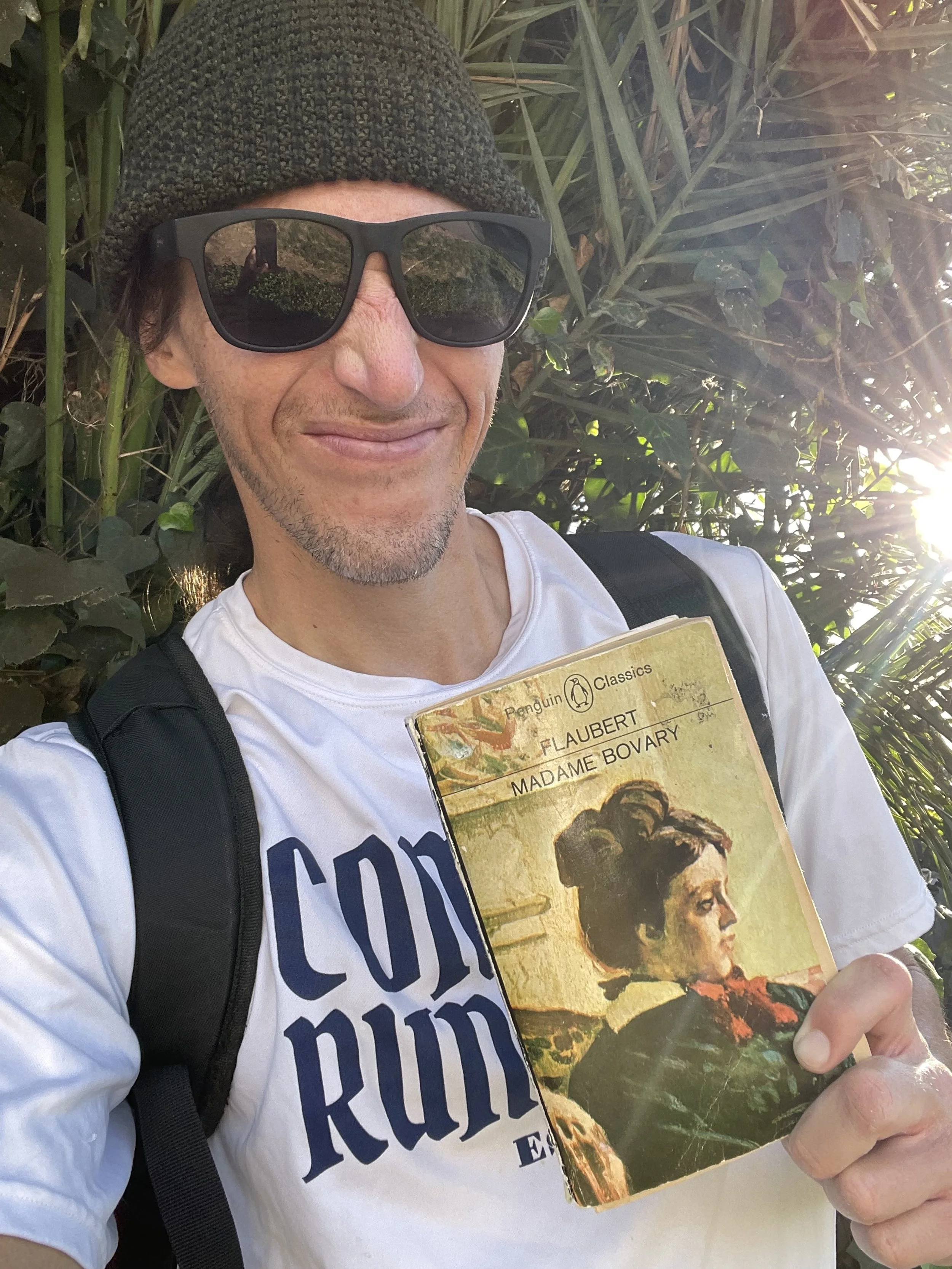

According to the introduction in the Penguin Classics edition I read (printed in Britain in 1950 (a great used book brings plenty of character, I enjoyed spending time with the 74-year-old edition I had to scotch tape together as I was reading it), Flaubert claimed “he would be ‘quite disgusted with life’ were he not engaged upon a novel.”

This dissatisfaction comes on like a silverback gorilla in Bovary, Flaubert never passing up a chance to embody a loud and massive patriarchic staking new territory through aggression in language and violence on his characters.

I’m sure the process of writing did good things for Flaubert, but I wince thinking how much worse a person this angry would be if they did not have a creative outlet for this energy.

That said, at times the raw angst in play hits targets I can nod with: privileged elites, who frame much of the conflict and motivation in Emma and Charles’ world, get bulls-eyed plenty, the social dynamics at a party of the privileged drawn with technique that is straight up awe-inspiring:

“Their nonchalant glances reflected the quietude of passions daily gratified; behind their gentleness of manner one could detect that peculiar brutality inculcated by dominance in not over-exacting activities such as exercise strength and flatter vanity - the handling of thoroughbreds and the pursuit of wantons.”

As graceful and precise as this passage is, bazookas become Flaubert elsewhere.

No member of his cast is safe from being reduced to ash in the surrounding population in Tostes, where Charles and the titular Emma Bovary settle down after a light-speed introduction, arrangement, and agreement of marriage, all with Emma’s nominal involvement.

For the author, this is a place that can’t present anything without some fault put under flood lights. His descriptions are downright giddy, only too ready to hold up one inadequacy and bad choice after another, exploring the repeated falls of each character, holding no cruelty back as each is dominoed down to add momentum to more collapses by people Flaubert is happy to kick and walk over.

The pharmacist Homais’ children are, for no reason, “grubby little urchins, badly brought up, and somewhat lethargic, like their mother.”

Hippolyte and the gangrene resulting from Charles’ mistaken treatment is mocked by everyone around around him.

On women in general: “their nervous system is so much more sensitive than ours."

Unsurprisingly, racism comes on strong, with characters complaining about the "carelessness of slaves” in seeing to duties they are forced into from birth.

A debt’s deadline is relaxed with the words, "there's no hurry. Any time will do. We're not Jews.”

Another character whines that they have gone unrecognized after having “worked like a million”-count of a word I’m not going to repeat, which is not the only time the word is used.

To be clear, any sentiment around “oh this was just how things were at the time” misses how those who have been brave and moral enough to stand against ugly status quos are the sole reasons why progress has been made towards equality.

Dismissing or defending such practices, then or now, does the opposite.

A mixed bag gets lopsided with elements like this, and context is essential, has to be looked at and turned over for a clear-eyed understanding of the time and work that have given us this time and work.

Flaubert’s powers are clear, but when his focus keeps to this monotony, degrading characters again, then again, pointing out faults, and showing them doing horrible things to each other, well.

Sure, no artist is beholden to anything, much less to love or even like the characters they’re writing about.

Indeed, the worst people, events, and subjects deserve as much attention as possible for reasons of justice and avoiding real-life repetition.

But to read someone curse and bash and sling mud with such passion and meanness is to try patience. I found an endurance test in Bovary which, on the bright side, adds an extra layer of iron to my stomach for digesting this sort of thing.

Flipping focus, a text this hurtful begs questions about what hurt Flaubert contained himself, and kept seeding more of the same.

Most telling, and maybe the most impactful, is the setting of an empty, useless standard in the following:

".... Homais concealed his emotion like a man.”

The cliché has and continues to permeate our world with the subtly of napalm, and gets laid out by Flaubert as a given that, clearly, it is not.

Inserted as it is in this foundational point in fiction and culture as a whole, the mind reels at the impact this one sentence has reaped, a quota of damage nutshelled in 7 words like an index fossil of an age still with us and certainly worth holding to the light, dressing down, and laughed at for its inherent insecurity and selection for cowardice over authenticity.

Combating this sentiment, we see another seed that sprouts much healthier and stronger roots and fruits in the opposite direction in the following:

“The yellow wallpaper behind her (Emma) gave her a sort of gold background, and her bare head was reflected in the mirror, with the white line of the parting in the middle and the tips of her ears peeping out from under the plaits of her hair,”

Then, a few lines later:

“‘If you only knew,’ she said, and she lifted her beautiful eyes to the ceiling as a tear formed, ‘if you only knew the dreams I’ve dreamed…’”

This very poignant meeting of images and subtext, I think, did much for Charlotte Gilman’s short story “The Yellow Wallpaper,” published in 1892. With Bovary published in 1857, I can see Gilman’s voice given flint to strike on, a baseline of suppression and dreams unrealized finding air and veritable forest fire in one of the best short stories we have, one in which the power of the female narrator in a world that has much in common with Emma Bovary’s grows, expands, and finds a vision of strength that can not be held back at all, regardless of the pressures and obstacles thrown her way.

In “The Yellow Wallpaper,” this conflict opts for a much different approach and battle than Emma seems interested in pursuing, either by being wholly unaware that options are on the table, which seems unlikely, or by Flaubert’s continuing portrayal and torture of characters he manifests in condescension, marches out in ridicule, and concludes in doom.

And yet, while it seems Emma’s values placed on societal standing and possessions are of such weight and size that to select anything else does not seem to enter possibility, there is a friction, without a doubt, a desire to find something more meaningful or interesting.

But, in action, any ambition Emma might have is channeled into the men around her, or longing for material wealth.

And, after financial ruin, Emma throws her last coin at an underprivileged “tramp” without eyes, Flaubert telling us this, “was the sum of her wealth; it seemed glorious to fling it away like that,” a relief, a burden vacated by rejecting the financial burdens that frame the majority of the pressures in the world of the novel.

I’m an optimist, so maybe, maybe there’s a spark of joy in there, somewhere, the one that comes with any act of helping someone in need.

But the scene and action moves forward too fast to give this element any air to breathe, much less grow, glossed over with Homais yelling advice back at the man, his own attempt at assistance, maybe promising, maybe seeded by Emma’s donation, one would hope.

The scene follows again with more digs at Emma, “the lust for profit running in her peasant blood,” which begs the question: is this opposed to every other class in the world of Bovary?

Are the slave-owning nobility above addiction to profit?

Or landowners? Farmers and religious officials?

Profit is the oasis for everyone in the parameters Flaubert creates in, but did not live in himself, never needing to worry about money himself, but all too ready to condemn anyone who actually had to be concerned for the welfare one obtains by no others means within the parameters of capitalism.

This is the case in Bovary, with a cast doomed to never be more than devices of punching down, hit over and over with fine technique, but wearingly so when its maker won’t allow for the game to be anything but a vessel for the darts he throws at targets he makes as big as the board.